If we want to continue to improve the UX maturity of our organization, we first need to be brutally honest about where we are on the totem pool, so we can plan strategically on how to increase our influence.

The problem is, we designers are often delusional. We confuse how we think the world works versus how the world actually works.

That’s why I always cringe a little bit when I hear designers use the word “should” when it comes to dealing with stakeholders.

They should follow the design spec! or…

They should come to us with a problem not the solution!

Nonsense, nobody should do anything unless it is The Law.

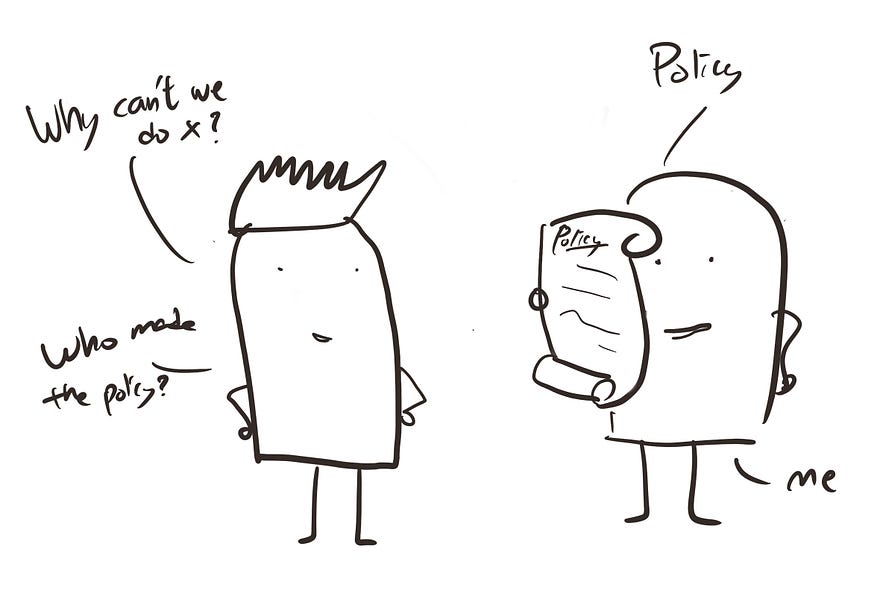

The word “should” implies a policy has already been established. It implies our idea of “how we want to do things” has been explicitly communicated, agreed upon, and documented with consensus from the other party, and now you are simply enforcing the policy as agreed.

When none of these has happened, your policy is not a widely accepted law, and you can’t expect other teams to follow it.

The design team’s influence reality check exercise

Here is an exercise you can do with your team for a reality check on how much influence the design team actually has in your company.

Look at your design policies and ask this simple question:

“Is this a House rule or the Law?”

House rules — are policies that only work within your social group, but have no effect on the outside world. In other words, only the design team cares, everybody else ignores this rule.

You can decide to play Monopoly however you want in your house amongst your friends, but if you play with strangers, they won’t follow your House rules.

If the designers agreed that “Pixel perfect is important” and every designer pays attention to it when they design, that is great! But if no one outside the design team cares, and if they don’t have to do what you say, it is a House rule, not The law.

The Law— Everybody has to obey this policy. In the real world, people have to obey the law or there will be consequences — like going to jail (well…at least in theory). For example, in my previous role at a bank, teams must meet a set of predefined accessibility requirements or the project won’t be allowed to go live (that means nobody gets their bonus).

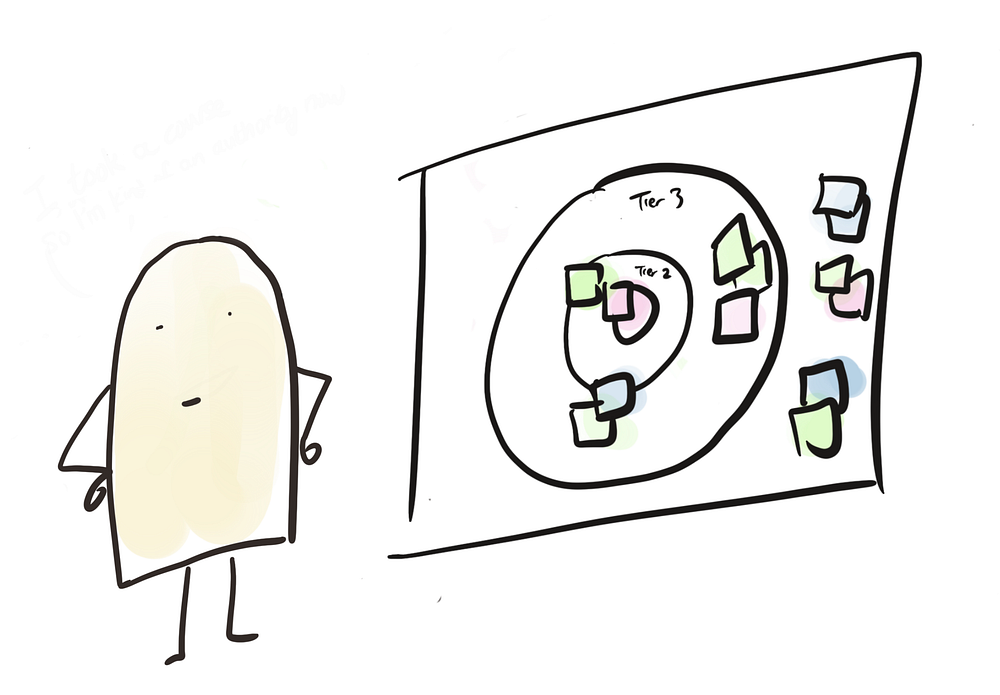

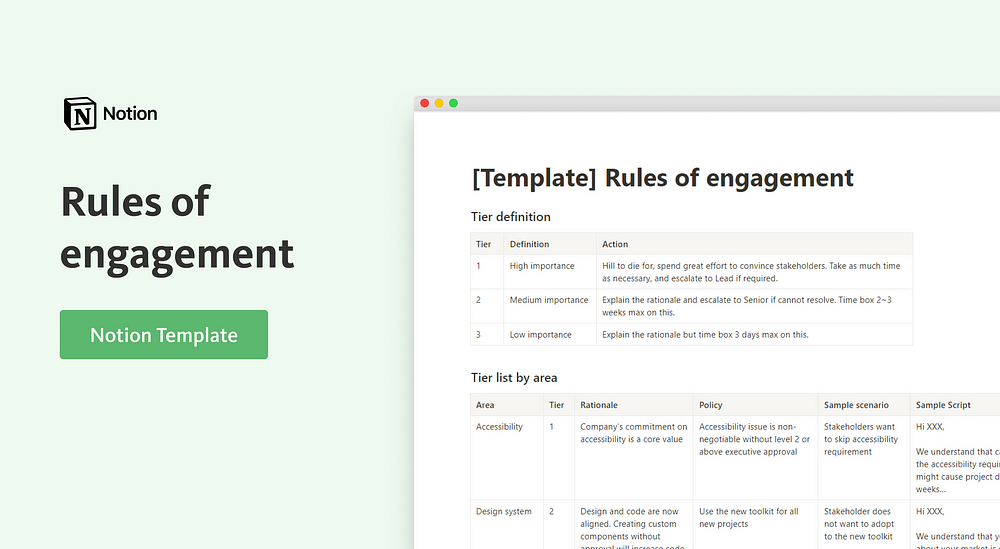

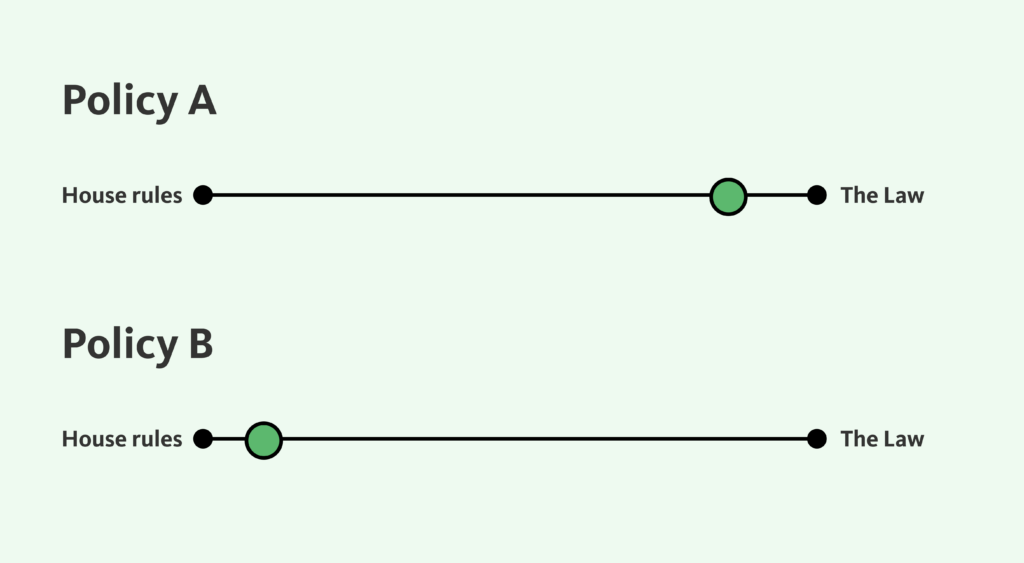

In reality, your design policies probably fall somewhere between these extremes. To visualize this, draw a line, and write “House rules” on the left and “The Law” on the right. List your important design policies and place them on a slider to determine their position between the two extremes. It should look something like this:

This is more art than science, the point is to do it with your team so you know which area is solid and which area needs work.

Now you have a visual representation of whether a policy is closer to a house rule where nobody cares, or closer to the law where everybody respects.

The idea is that the more design policies you have that are on the right side of the spectrum, the higher the influence the design team has in the organization.

If you are an aspirational design leader, one of your high-leverage activities is to look at how many design policies you wish to turn from “House rules” into “The Law”, prioritize them, then lobby them one at a time.

Hope this exercise brings clarity to your design organization and good luck!